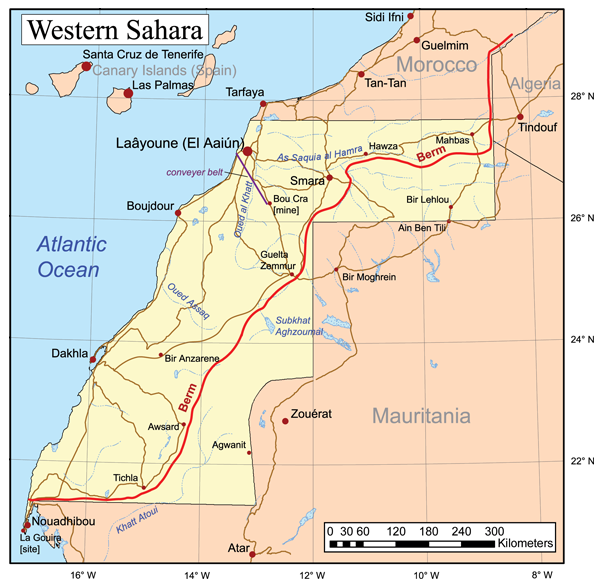

Western Sahara is a sparsely populated region in northwest Africa, stretching over 266,000 square kilometers, marked by deserts and arid landscapes. Bordered by Morocco to the north, Algeria to the northeast, Mauritania to the east and south, and the Atlantic Ocean to the west.

The region is economically relevant, mainly because of its substantial phosphate reserves—a raw material for fertilizers—and potential offshore natural gas reserves. These resources make Western Sahara important locally and a point of interest for many countries and populations in the region, which contribute to the longstanding dispute over its sovereignty.

The conflict in Western Sahara began in the mid-20th century, but intensified in the 1970s when Spain, the colonial power at the time, started withdrawing from the region. This vacuum led to a dispute primarily between Morocco and the Polisario Front, which represented the indigenous Sahrawi people.

Morocco claims Western Sahara as an integral part of its kingdom, citing historical ties to the region before Spanish colonization. The Moroccan government argues that its sovereignty over the area is a matter of national integrity and has pursued a policy of settlement and economic investment to reinforce its claim.

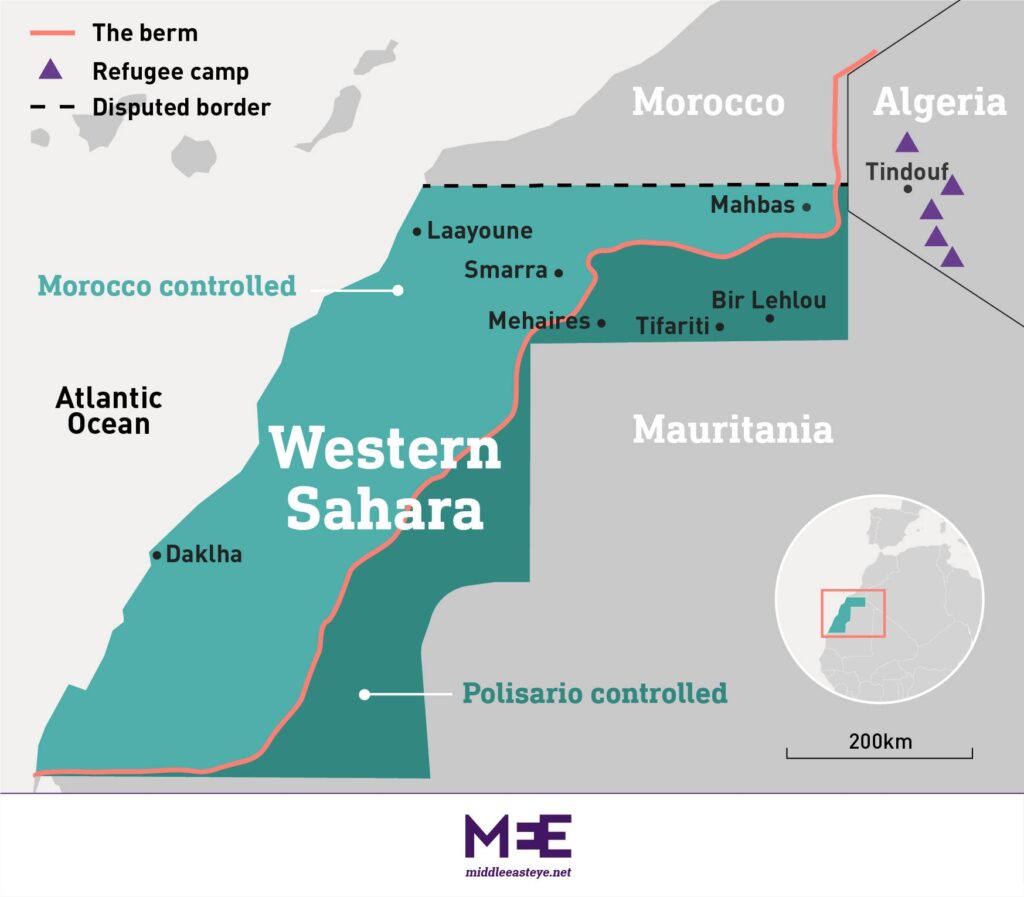

The Polisario Front, on the other hand, seeks an independent state and has established the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic (SADR), which controls part of the territory, mostly the area east of the Moroccan-built sand wall, known as the Berm.

Disclaimer: I’m not an expert in geopolitical analysis, in this post, I’ll summarize my understanding of the historical context and current state of the Western Sahara conflict. Feel free to leave feedback and point out imprecisions that this post might contain.

Economic Significance

Before diving into the historical facts, it’s important to understand why many people are interested in this area and why it matters. Western Sahara holds considerable economic value, primarily due its rich natural resources.

The region contains one of the world’s largest deposits of phosphates, concentrated at the Bou Craa mine. This mine alone contributes to the global phosphate market, which makes Morocco the largest exporter of the material, or the largest competitor to Morocco, if controlled by other people. Also, the region is believed to contain offshore natural gas reserves in its exclusive economic zone, if proven and exploited, could be a game-changer for the energy sector in North Africa and potentially supply energy to European markets.

Both of those factors, combined with a coastline along the Atlantic Ocean, position it as an strategic asset to whoever has sovereignty over Western Sahara.

Historical Context

The Scramble for Africa, in the late 19th century, is a good moment to start looking at Western Sahara’s story. Spain claimed the region, and called it Spanish Sahara. The Spanish focused on the areas along the coast and places rich in phosphates, while leaving the remaining areas to its own devices.

When countries in Africa started gaining independence from colonial powers, the uncertainties in the region started to rise. Morocco and Mauritania, becoming independent, claimed they had historical ties to the region, with Morocco arguing that the region was part of its territory before Spain took over.

In 1975, the International Court of Justice looked into these claims. While they recognized some cultural ties between Moroccan tribes and the Sahrawi people, they didn’t see this as enough to grant Morocco rights over the area. Despite this, Moroccan King Hassan II organized the Green March, where 350,000 Moroccans peacefully entered Western Sahara, pressuring Spain to leave. This led to the Madrid Accords where Spain agreed to hand over the territory to Morocco and Mauritania, without considering the Sahrawi people.

As the Spanish prepared to leave, the Polisario Front, a group formed by Sahrawis who wanted independence, declared their own government and called the region the Sahrawi Arab Democratic Republic in 1976. The Polisario Front started fighting against Moroccan and Mauritanian forces. Mauritania left the conflict in 1979, but Morocco continued to be involved in the conflict. As Morocco had a presence in the region, they built a huge sand wall, called the Berm, which cuts off Moroccan controlled areas from the rest of Western Sahara.

The fighting led to a ceasefire in 1991, with the United Nations stepping in to help organize a vote on independence. The disagreements on who should be allowed to vote have kept a referendum from happening. The UN still has forces in the area, but a definitive solution hasn’t been found yet.

The Ongoing Conflict

Even though the fighting between Morocco and the Polisario Front has cooled down since the ceasefire in 1991, the conflict over the Western Sahara is far from being resolved.

The main point of the disagreement remains the referendum on Western Sahara’s independence, promised by the UN but never put into practice. Morocco and the Polisario Front disagree over who should be eligible to vote. Morocco wants settlers who moved in after the Green March to be included, while the Polisario insists that only the original Sahrawi people and their direct descendants should be eligible to vote. This disagreement prevents a referendum from happening.

The Polisario Front, backed by Algeria, hasn’t been on waiting mode. They’ve declared a government-in-exile, from Tindouf, Algeria, and gained recognition from some countries and organizations. They continue to advocate for independence and maintain a military presence, although reduced since the ceasefire. Periodically demonstrations and other minor events raise tensions at the Berm.

The international response is mixed. Some countries support Morocco’s claim, such as the United States, in exchange for Morocco normalizing relationships with Israel, as part of Abraham Accords to stabilize relations in the Middle East. Other countries, such as Algeria and South Africa support the Polisario Front. European countries also have a mixed view of the conflict. France, due to its proximity and ties sides with Morocco, while Spain being neutral and calling for a mutually acceptable solution facilitated by the United Nations.

In 2020, the conflict heated up again when Moroccan troops entered a buffer zone of Guerguerat to restore free circulation, renewing the tension. The Polisario Front declared that the ceasefire was broken, but that hasn’t led to any major hostilities. The UN and other international bodies have called for restraint and a return to negotiations, but progress has been slow.

Next Steps

The path to a resolution of this conflict remains stuck with complexity and competing interests.

Morocco has proposed a plan for autonomy under Moroccan sovereignty, which would grant Western Sahara a degree of self-governance while still recognizing Moroccan control over the territory. This proposal has received support from some key international actors but is rejected by the Polisario Front, which continues to demand full independence.

The original UN plan for a referendum on self-determination has been stalled due to disagreements over who is eligible to participate. The Polisario Front advocates for a voting process that includes only those residents who lived in the territory before the Moroccan annexation in 1975 and their descendants. This could provide a democratic resolution to the conflict, but Morocco has consistently rejected this alternative.

The future of Western Sahara remains uncertain. It’s a complex scenario given its historical factors, geopolitical, and economic interests of many parties involved in the region. A lasting solution will require patience and commitment. The world needs to support a solution that respects the different peoples and their interests in a way that helps the region to reach a peaceful stability and prosperity.